Can deep-sea nodules solve the critical minerals barrier to a low-carbon energy future?

Sucking up concentrated nodules of critical minerals from the ocean depths could help tackle one of the bottlenecks facing renewable energy, but battle lines are drawn

An ambitious plan to harvest metals-rich nodules from the abyssal seafloor of the Pacific Ocean will be in the spotlight next week as the International Seabed Authority (ISA) meets in Kingston, Jamaica to consider long-awaited draft regulations for mining activities on the ocean floor.

The controversial new rules have run into resistance as several of the intergovernmental body’s member states have sought more time to study the environmental effects of seabed mining.

Supporters say they have a compelling argument in favour of mining for deep-sea minerals, insisting that the rare metals are vital to the energy transition and that activities can be carried out on the seafloor with less environmental or social impact than land-based mining.

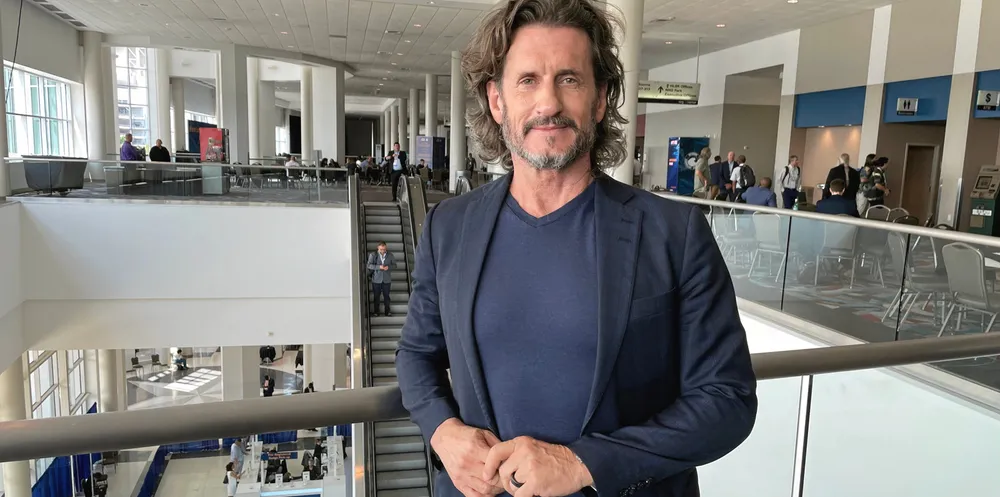

That was the line Gerard Barron took speaking before an audience predominantly made up of oil and gas professionals at the Offshore Technology Conference in Houston in May.

Barron, chief executive of The Metals Company (TMC), says a recent pilot test using a converted ultra-deepwater drillship and collection system to lift polymetallic nodules from 4300-metre depths in the eastern Pacific Ocean will help launch an industry long talked about but now given more impetus in the transition to cleaner energy.

<b>Polymetallic nodules</b>

Polymetallic or manganese nodules are formed over millions of years and lie unattached to the abyssal seafloor.The nodules typically contain cobalt, nickel and manganese, used in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicle batteries or energy storage, as well as copper, which is crucial to the speedy build-out of transmission and distribution lines needed to connect renewable power sources to grids

Producing metals from nodules leaves very little waste and, unlike land ores, they do not contain toxic levels of heavy elements, Barron says.

They are also found far from land with less impact on biodiversity or people than land mining sites.

“Mining impacts people. It impacts indigenous communities. It impacts people who don’t want mining,” Barron says, conjuring up images of cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo or nickel mines in Indonesia.

“If you go to Indonesian villages, they’re not looking to drive electric cars. They may not want these mines, but typically the licences go to foreign corporations… and they carry out practices that would be illegal even back in their own countries.”

Environmental impact

Scientists have been analysing data collected during the two-month pilot test conducted late last year in the nodule-rich Clarion Clipper Zone (CCZ) between Hawaii and Mexico.

TMC subsidiary Nauru Ocean Resources Incorporated (Nori) is using the data to prepare an environmental impact statement and plans to submit an application later this year for a contract to mine the NORI-D area of the CCZ.

Switzerland-headquartered offshore construction company Allseas partnered with Nori in the pilot, acquiring and converting the drillship Hidden Gem for the mission and building an innovative collection system to bring the nodules to the surface.

The pilot involved up to 50 vessels, autonomous underwater vehicles and remotely operated vehicles to monitor the operation and collect data.

Allseas declared the operation a “milestone” for the company and the nascent industry, proving the viability of seabed nodule collection 150 years after polymetallic nodules were identified as a potential resource.

In total, about 4,500 tonnes of nodules were collected, and 3,000 tonnes brought to the surface via a 4.3-kilometre riser and stored in the hull of the production vessel, the Hidden Gem.

The additional 1,500 tonnes of nodules were purposely left behind on the seafloor as part of the trials.

The successful pilot came after many years of research and development between the offshore engineering and construction stalwart and Nori, says Allseas manager of corporate communications Jeroen Hagelstein.

Around 2017, Barron, then chief executive of TMC forerunner DeepGreen, approached Allseas' Dutch founder Edward Heerema about developing the technologies and building the equipment required to collect the nodules and bring them to the surface.

“We had the concept and how we thought it would work in mind,” Hagelstein says.

Allseas took a stake in the company and increased it in 2021, when DeepGreen listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange as The Metals Company.

Hidden Gem

“The drillship was interesting to us because it had the moonpool and a big drilling tower, knowing that we would have to build a riser that length,” Hagelstein says.

The company “had never built something like this”, he notes, but was accustomed to working at great water depths and for challenging pipeline construction projects.

“It was something that we were confident we could do, but it was a new chapter for us to develop and build this technology,” he says.

The self-propelled collector vehicle had to be engineered to be light enough not to sink into the soft seabed yet heavy enough to remain submerged.

And the entire system had to withstand extreme water pressure at 4,300-metre depths.

Driving over 80km on the seabed, the collector vehicle reached a sustained production rate of 86.4 tonnes per hour during the trial.

All parts of the system are to be scaled up for commercial operations — including a collector vehicle 2.5 times larger than the pilot version — but the company is waiting for the ISA to rule on the mining code before proceeding.

“By the end of next year, we will be ready to start commercial mining,” Hagelstein says.

Commercial scale-up

Barron hopes to launch small-scale commercial production of about 1 million tonnes per annum in 2024, scaling up to 10 million tpa in 2025.

While seabed mining has drawn fire from environmentalists, Barron insists the high level of monitoring and vast data-gathering — and a “relatively two-dimensional” mining method that does not involve digging — give nodules an advantage.

“We would argue that you should look through the lens of the life-cycle analysis of all projects,” he said. “There are some projects on land that have acceptable risks. There are many that do not.”

He added: “It is true that we do have a footprint, but there is no alternative use for this area, whereas on land you have competing interests.”

The upcoming ISA rules have drawn attention from both supporters and opponents of seabed mining.

Last month, the US House of Representatives’ Armed Services Committee included polymetallic nodules in a spending request that includes a roadmap on how the US “can have the ability to source and/or process critical minerals in innovative arenas, such as deep-sea mining, to decrease reliance on sources from foreign adversaries and bolster domestic competencies”.

Barron has previously sought support from US officials by portraying the mining of polymetallic nodules as vital to the nation’s national security interests and energy transition ambitions, telling the Senate Energy & Natural Resources Committee in a letter last year that support from the US — which is not an ISA member — “would unlock access to the resource without overcoming legislative hurdles to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”.

He has found a friend in Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, who has urged the US Department of Energy to “explore the potential” of polymetallic nodules from the CCZ as a source of critical battery minerals.

Further studies

Many scientists and environmental advocates say more research needs to be done before commercial mining in the CCZ starts up, however.

A recent study published in the journal Current Biology found that an estimated 92% of the nearly 5600 species identified to date in the area “are new to science” and authors called for more data to be gathered before proceeding.

The ISA has established protected “areas of particular environmental interest” adjacent to the proposed mining sites.

Barron insists that TMC is investing heavily in monitoring systems that will serve as “eyes and ears for the regulator and civil society so people can see what we’re doing”, and that the company will participate in ongoing studies to gauge the effects of its activities on the CCZ environment.

Mining for battery minerals, whether on land or four kilometres below the Pacific Ocean surface, will be necessary to “get where we need to” in lowering emissions, he says.

“In a perfect world, we would stop all extractive industries, right? But we don’t live in a perfect world. We live in a world where we need to make choices and compromises.”